Blog

Back to main | List of entries |

Joints of varieties

September 12, 2020

The summer has come to an end. The temperature in Boston seems to have dropped all the sudden. Our fall semester has just started, though without all the new and returning students roaming around campus this time (most classes are online this term). I quite miss the view from my MIT office, and all the wonderful people that I would run into the department corridors.

I’ve been working from home for the past several months and connecting with my students via Zoom. In this and the upcoming several posts, I would like to tell you about some of the things that we have been working on recently.

With PhD student Jonathan Tidor and undergraduate student Hung-Hsun Hans Yu, we recently solved the joints problem for varieties by a developing a new extension of the polynomial method. (Also see my talk video and slides on this work.)

I discussed the joints problem in an earlier blog post. Recall that the joints problem asks:

Joints problem: At most how many joints can $N$ lines in $\mathbb{R}^3$ can make?

Here a joint is a point contained in three non-coplanar lines.

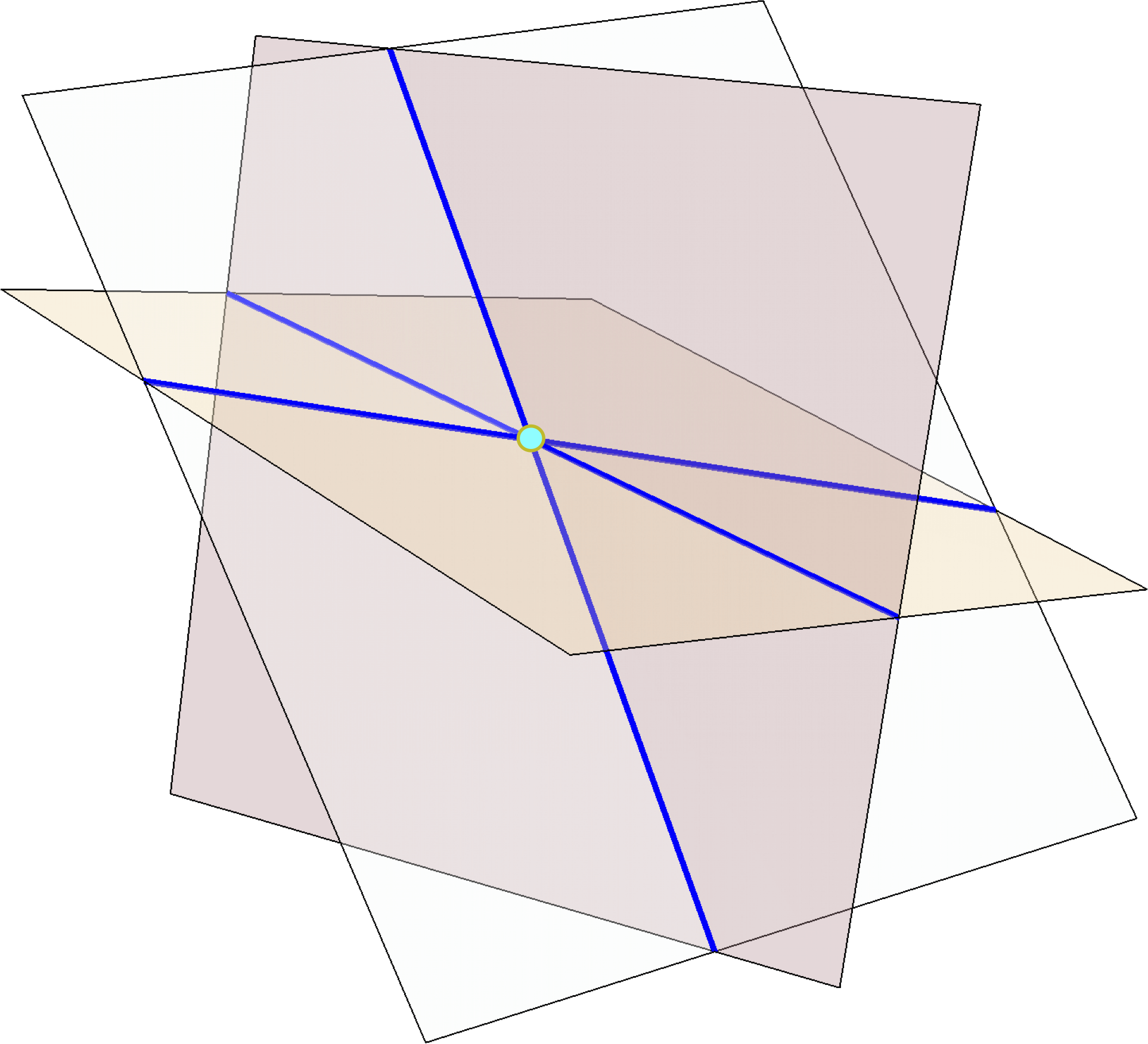

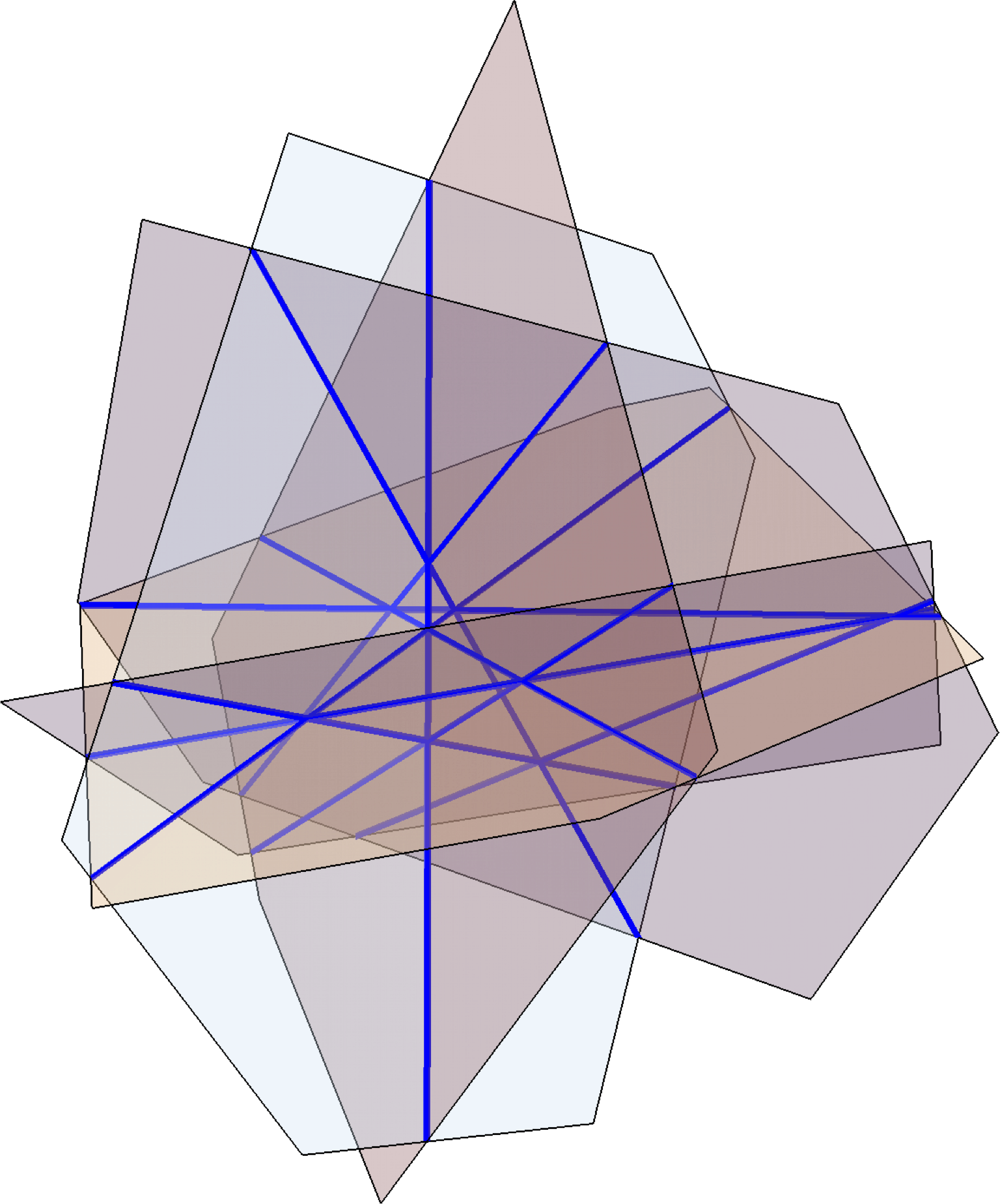

Here is an example of a configuration of lines making many joints. Take k generic planes in space, pairwise intersect them to form \(N = \binom{k}{2}\) lines, and triplewise intersect to form \(J = \binom{k}{3} \sim \frac{\sqrt{2}}{3} N^{3/2}\) joints.

The joints problem was raised in the early 1990’s. It is a problem in incidence geometry, which concerns possible incidence patterns of objects like points and lines. The joints problem has also received attention from harmonic analysts due to its connections to the Kakeya problem.

The big breakthrough on the joints problem was due to Guth and Katz, who showed that the above example is optimal up to a constant factor:

Joints theorem (Guth–Katz). $N$ lines in \(\mathbb{R}^3\) form $O(N^{3/2})$ joints.

Guth and Katz solved the problem using a clever technique known as the polynomial method, which was further developed in their subsequent breakthrough on the Erdős distinct distances problem. The polynomial method has since then grown into a powerful and indispensible tool in incidence geometry, and it also led to important recent developments in harmonic analysis.

I learned much of what I know about the polynomial method from taking a course by Larry Guth while I was a graduate student. Guth later developed the course notes into a beautifully written textbook, which I highly recommend. A feature of the expository style of this book, which I wish more authors would adopt, is that it frequently motivates ideas by first explaining false leads and wrong paths. As I was reading this book, I felt like that I was being taken on a journey as a travel companion and given a lens towards the thinking process, rather than somehow being magically teleported to the destination.

In my previous paper on the joints problem with Hans Yu, which I discussed in earlier blog post, we sharpened the Guth–Katz theorem to the optimal constant.

Theorem (Yu–Zhao). $N$ lines in \(\mathbb{R}^3\) have \(\le \frac{\sqrt{2}}{3} N^{3/2}\) joints.

Everything I have said so far are also true in arbitrary dimensions and over arbitrary fields, but I am only stating them in \(\mathbb{R}^3\) here to keep things simple and concrete.

Joints of flats

Our new work solves the following extension of the joints problem.

Joints problem for planes. At most how many joints can $N$ planes in \(\mathbb{R}^6\) make?

Here a joint is a point contained in a triple of 2-dimensional planes not all contained in some hyperplane.

The example given earlier for joints of lines extends easily to joints of planes.

Example. Take $k$ generic 4-flats in \(\mathbb{R}^6\), pairwise intersect them to form $N = \binom{k}{2}$ planes, and triplewise intersect them to form \(\binom{k}{3} = \Theta(N^{3/2})\) joints.

Joints of planes concerns incidences between high dimensional objects, which in general tend to be more intricate compared to incidence problems about points and lines.

I first learned about this problem from a paper of Ben Yang, who did this work as a PhD student of Larry Guth. Yang proved that $N$ planes in \(\mathbb{R}^6\) form at most $N^{3/2+o(1)}$ joints. His proof uses several important recent developments in incidence geometry, and in particular uses the polynomial partitioning technique of Guth and Katz (as well as subsequent extensions due to Solymosi–Tao and Guth). This is a fantastic result, though with two important limitations due to the nature of the method:

- There is an error term in the exponent $N^{3/2+o(1)}$ that is conjectured not to be there. One would like a bound of the form $O(N^{3/2})$

- The result is restricted to planes in \(\mathbb{R}^6\) and does not work if we replace \(\mathbb{R}\) by an arbitrary field. This is because the polynomial partitioning method uses topological tools, in particular the ham sandwich theorem, which crucially requires the topology of the reals.

Our work overcomes both difficulties. As a special case, we prove (here \(\mathbb{F}\) stands for an arbitrary field, and the hidden constants do not depend on \(\mathbb{F}\)):

Joints of planes (Tidor–Yu–Zhao). $N$ planes in \(\mathbb{F}^6\) have $O(N^{3/2})$ joints.

And more generally, our results hold for varieties instead of flats. Here a joint is a point contained in a triple of varieties, such that it is a regular point on each of the three varieties and the three tangent plane do not lie inside a common hyperplane.

Joints of varieties (Tidor–Yu–Zhao). A set of 2-dimensional varieties in \(\mathbb{F}^6\) of total degree $N$ has $O(N^{3/2})$ joints.

The above statements are special cases of our results. The joints problem for lines is known to hold under various extensions (arbitrary dimension and fields, several sets/multijoints, counting joints with multiplicities), and our theorem holds in these generalities as well.

Proof sketch of the joints theorem for lines

Here is a sketch of the proof that $N$ lines in \(\mathbb{R}^3\) make $O(N^{3/2})$ joints (following the simplifications due to Kaplan–Sharir–Shustin and Quilodrán; also see Guth’s notes for details of the proof).

The first two steps below are both hallmarks of the polynomial method, and they are present in nearly every application of the method. The third step is a more joints-specific argument.

-

Parameter counting. The dimension of the vector space of polynomials in \(\mathbb{R}[x,y,z]\) up to degree $n$ is \(\binom{n+3}{3}\). We deduce that if there are $J$ joints and \(J < \binom{n+3}{3}\), then one can find a nonzero polynomial $g$ of degree $\le C J^{1/3}$ (for some constant $C$) that vanishes on all the joints (as there are more coefficients to choose from than there are linear constraints). Take such a polynomial $g$ with the minimum possible degree.

-

Vanishing lemma. A nonzero single variable polynomial cannot vanish more times than its degree.

-

If all lines have $> CJ^{1/3}$ joints, then the vanishing lemma implies that $g$ vanishes on all the lines. At each joint, $g$ vanishes identically along three independent lines, and hence its directional derivatives vanish in three independent directions, and thus the gradient \(\nabla g\) vanishes at the joint. Therefore, the three partial derivatives \(\partial_x g\), \(\partial_y g\), \(\partial_z g\) all vanish at every joint, and at least one of them is a nonzero polynomial and has smaller degree than $g$, thereby contradicting the minimality of the degree of $g$. Therefore, the initial assumption must be false, namely that some line has \(\le C J^{1/3}\) joints. We can then remove this line, deleting \(\le CJ^{1/3}\) joints, and proceed by induction to prove that $J = O(N^{3/2})$.

Some wishful thinking

It is natural to try to extend the above proof for the joints problem for planes. One quickly runs into the following conundrum:

How does one generalize the vanishing lemma to 2-variable polynomials?

The vanishing lemma is such an elementary fact about how polynomial behaves on a line. Yet it plays a crucial role in the polynomial method. We would be able to adapt the above proof to joints of planes if only something like the following would be true (they are not):

Wishful thinking 1. Show that every nonzero polynomial $g(x,y)$ of degree $n$ has $O(n^2)$ zeros.

Well, this is obviously nonsense. The zero set of $g(x,y)$ is typically a curve with infinitely many points.

How else might we try to extend the vanishing lemma to two dimensions? Bézout’s theorem is one such extension. It tells us that two polynomials $g(x,y)$ and $h(x,y)$ without common factors cannot have more than $(\deg g)(\deg h)$. So, perhaps, instead of trying to find one polynomial vanishing at all joints, we try to find a pair of polynomials.

Wishing thinking 2. Show that one can find two polynomials \(g, h \in \mathbb{R}[x_1, x_2, x_3, x_4, x_5, x_6]\) vanishing at all $J$ joints and $(\deg g)(\deg h) = O(J^{1/3})$, and such that $g$ and $h$ have no common factors when restricted to any of the given planes.

This approach is a natural one to try for the joints of planes problem, and is an approach that many people have thought about. It also seems extremely hard to get it to work (likely impossible). It seems closely related to the inverse Bézout problem, which already illustrates some of the difficulties encountered.

Instead of asking a polynomial to vanish at every joint, we can demand more. Namely that we can ask the polynomial to vanish at each joint to some high order (equivalently, asking some derivatives of the polynomial to vanish at the joints). This idea (sometimes called the “method of multiplicities”) has shown to be useful in a variety of contexts. Perhaps we can modify Wishing thinking 1 to account for these multiplicities?

Wishful thinking 3. Show that every nonzero polynomial $g(x,y)$ of degree $n$ can vanish to order $s$ at no more than $O(n^2/s^2)$ points.

The reason why one might hope for such a statement is that there are \(\binom{n+2}{2} \approx n^2/2\) degrees of freedom for choosing $g$, and this number is roughly the same as the number of constraints associated to forcing the polynomial to vanish to order $s$ at $n^2/s^2$ points.

However, Wishful thinking 3 is still too good to be true. For example, the polynomial $g(x,y) = y^s$ is a low-degree polynomial that vanishes to order $s$ at every point on the $x$-axis.

So what was wrong with the parameter counting intuition? It must be the case that some of the linear constraints associated to these high order vanishing constraints are linearly dependent.

Extending the polynomial method

So far all I have told you are what doesn’t work, and I haven’t said anything about what does work. Where we left off above is a good starting point of what we actually do, which I will not describe here in this blog post but instead refer you to either my talk or our paper for details. We have to account for the linear dependencies between these higher order vanishing conditions, and we come up with a process of assigning non-redundant vanishing conditions (each in the form of some higher order derivative operator evaluated at a joint). We prove a new vanishing lemma tailored for this joints problem. Rather vaguely, it has the following form:

A new vanishing lemma. Given a finite set of planes in \(\mathbb{R}^6\) forming some joints, and a positive integer $n$, and an integer (“handicap”) attached to each joint, we run a certain process that assigns, on each plane, a total of \(\binom{n+2}{2}\) derivative operators across the joints on this plane. Then for every nonzero polynomial \(g(x_1, \dots, x_6)\) of degree at most $n$, there is some joint $p$, three planes $F_1, F_2, F_3$ containing $p$, and a derivative operator $D_i$ assigned to $p$ on $F_i$ through our process for each $i =1,2,3$, so that $D_1 D_2 D_3 g(p) \ne 0$.

This new vanishing lemma overcomes the earlier difficulty and allows us to extend the polynomial method to solve the joints problem for planes.

Let me finish with an open problem: while we can prove the optimal constant for the joints theorem for lines, we do not yet know how to prove the optimal constant for the joints theorem for planes.

Conjecture. $N$ planes in \(\mathbb{F}^6\) have \(\le (\frac{\sqrt{2}}{3} + o(1)) N^{3/2}\) joints.

Back to main | List of entries |

More posts:

- Mehtaab Sawhney wins Clay Research Fellowship 1/25/2024

- Papers by MIT combinatorialists—Fall 2023 12/22/2023

- Schildkraut: Equiangular lines and large multiplicity of fixed second eigenvalue 3/6/2023

- Nearly all k-SAT functions are unate 9/19/2022

- Kwan–Sah–Sawhney–Simkin: High-girth Steiner triple systems 1/13/2022

- Graphs with high second eigenvalue multiplicity 9/28/2021

- Enumerating k-SAT functions 7/21/2021

- Mathematical tools for large graphs 7/12/2021

- How I manage my BibTeX references, and why I prefer not initializing first names 7/4/2021

- The cylindrical width of transitive sets 1/28/2021

- Ashwin Sah and Mehtaab Sawhney win the Morgan Prize 10/29/2020

- Jain–Sah–Sawhney: Singularity of discrete random matrices 10/13/2020

- Gunby: Upper tails for random regular graphs 10/5/2020

- Joints of varieties 9/12/2020

- Ashwin Sah's new diagonal Ramsey number upper bound 5/20/2020

- Joints tightened 11/21/2019

- Equiangular lines with a fixed angle 7/30/2019

- Impartial digraphs 6/27/2019

- A reverse Sidorenko inequality 9/26/2018

- The number of independent sets in an irregular graph 5/12/2018