Blog

Back to main | List of entries |

Mathematical tools for large graphs

July 12, 2021

Author’s note: This article was written intended for a general scientific audience.

Graphs and networks form the language and foundation of much of our scientific and mathematical studies, from biological networks, to algorithms, to machine learning applications, to pure mathematics. As the graphs and networks that arise get larger and larger, it is ever more important to develop and understand tools to analyze large graphs.

Graph regularity lemma

My research on large graphs has its origins in the work of Endre Szemerédi in the 1970s, for which he won the 2012 Abel Prize, a lifetime achievement prize in Mathematics viewed as equivalent to the Nobel Prize. Szemerédi is a giant of combinatorics, and his ideas still reverberate throughout the field today.

(Photo from the Abel Prize)

Szemerédi was interested in an old conjecture of Paul Erdős and Pál Turán from the 1930s. The conjecture says that

if you take an infinite set of natural numbers, provided that your set is large enough, namely that it occupies a positive fraction of all natural numbers, then you can always find arbitrarily long arithmetic progressions.

For instance, if we take roughly one in every million natural numbers, then it is conjectured that one can find among them k numbers forming a sequence with equal gaps, regardless of how large k is.

This turns out to be a very hard problem. Before the work of Szemerédi, the only partial progress, due to Fields Medalist Klaus Roth in the 1950’s is that one can find three numbers forming a sequence with equal gaps. Even finding four numbers turned out to be an extremely hard challenge until Szemerédi cracked open the entire problem, leading to a resolution of the Erdős–Turán conjecture. His result is now known as Szemerédi’s theorem. Szemerédi’s proof was deep and complex. Through his work, Szemerédi introduced important ideas to mathematics, one of which is the graph regularity lemma.

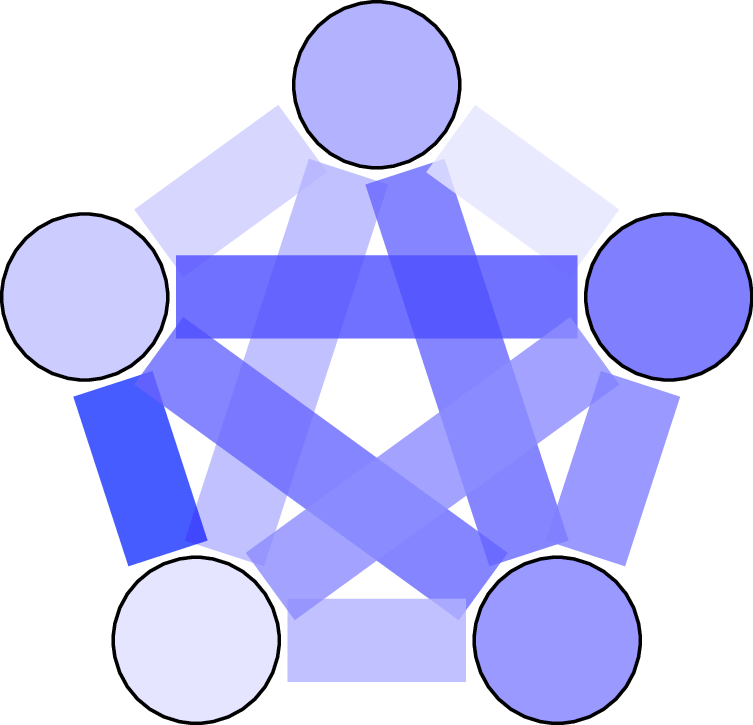

Szemerédi’s graph regularity lemma is a powerful structural tool that allows us to analyze very large graphs. Roughly speaking, the regularity lemma says that

if we are given a large graph, no matter how the graph looks like, we can always divide the vertices of the graph into a small number of parts, so that the edges of the graph look like they are situated randomly between the parts.

Between different pairs of parts of vertices, the density of edges could be different. For example, perhaps there are five vertex parts A, B, C, D, E; between A and B the graph looks like a random graph with edge density 0.2; between A and C the graph looks like a random graph with edge density 0.5, and so on.

An important point to emphasize is that, with a fixed error tolerance, the number of vertex parts produced by the partition does not increase with the size of the graph. This property makes the graph regularity lemma particularly useful for very large graphs.

Szemerédi’s graph regularity lemma provides us a partition of the graph that turns out to be very useful for many applications. This tool is now a central technique in modern combinatorics research.

A useful analogy is the signal-versus-noise decomposition in signal processing. The “signal” of a graph is its vertex partition together with the edge density data. The “noise” is the residual random-like placement of the edges.

Szemerédi’s idea of viewing graph theory via the lens of this decomposition has had a profound impact in mathematics. This decomposition is nowadays called “structure versus pseudorandomness” (a phrase popularized by Fields Medalist Terry Tao). It has been extended far beyond graph theory. There are now deep extensions by Fields Medalist Timothy Gowers to what is called “higher order Fourier analysis” in number theory. The regularity method has also been extended to hypergraphs.

Graph limits

László Lovász, who recently won the 2021 Abel Prize, has been developing a theory of graph limits with his collaborators over the past couple of decades. Lovász’s graph limits give us powerful tools to describe large graphs from the perspective of mathematical analysis, with applications ranging from combinatorics to probability to machine learning.

Why graph limits? Here is an analogy with our number system. Suppose our knowledge of the number line was limited to the rational numbers. We can already do a lot of mathematics with just the rational numbers. In fact, with just the language of rational numbers, we can talk about irrational numbers by expressing each irrational number as a limit of a sequence of rational numbers chosen to converge to the irrational number. This can be done but it would be cumbersome if we had to do this every time we wanted to use an irrational number. Luckily, the invention of real numbers solved this issue by filling the gaps on the real number line. In this way, the real numbers form the limits of rational numbers.

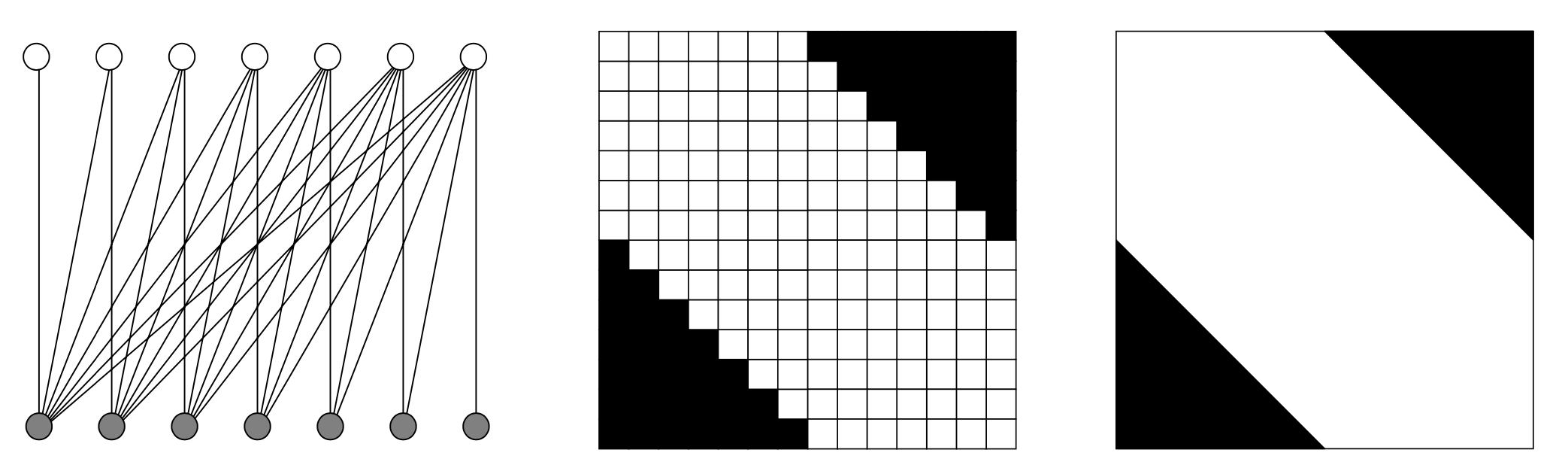

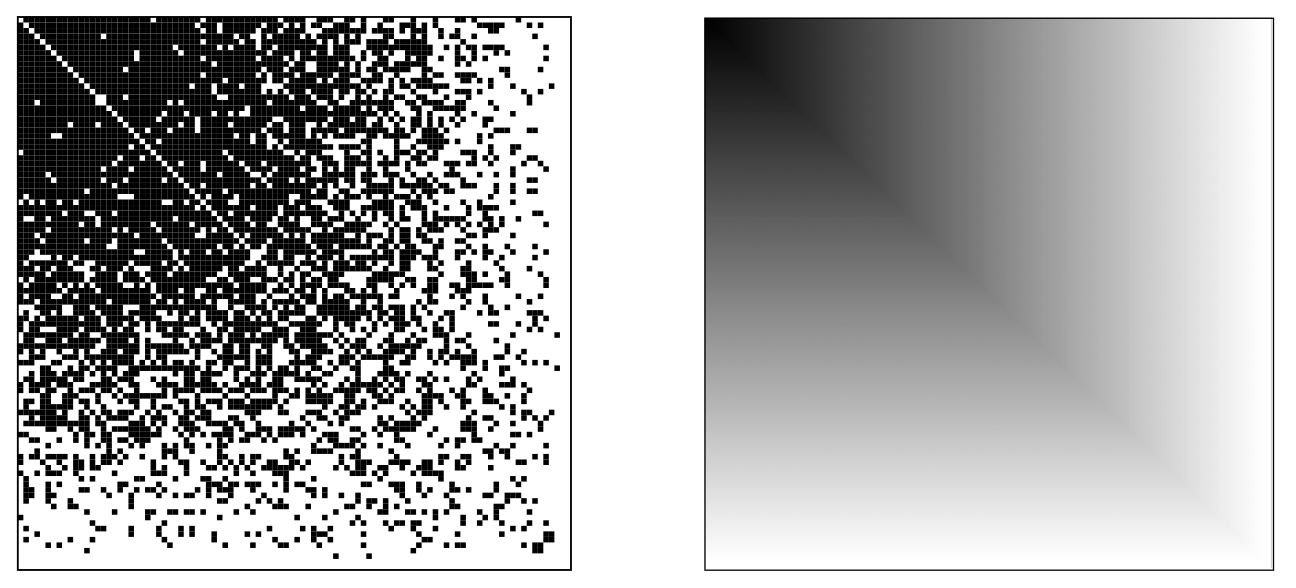

Likewise, graphs are discrete objects analogous to rational numbers. A sequence of graphs can also converge to a limiting object (what does it mean for a sequence of graphs to converge is a fascinating topic and beyond the scope of this article). These limiting objects are called “graph limits,” also known as “graphons.” Graph limits are actually simple analytic objects. They can be pictured as a grayscale image inside a square. They can also be represented as a function from the unit square to the unit interval (the word “graphon” is an amalgamation of the words “graph” and “function”). Given a sequence of graphs, we can express each graph as an adjacency matrix drawn as a black and white image of pixels. As the graphs get larger and larger, this sequence of pixel images looks closer and closer to a single image, which might be not just black and white but also could have various shades of gray. This final image is an example of a graph limit. (Actually, there are subtleties here that I am glossing over, such as permuting the ordering of the vertices before taking the limit.)

(Both images taken from Lovász’s book)

Conversely, given a graph limit, one can use it as a generative model for random graphs. Such random graphs converge to the given graph limit when the number of vertices increases. This random graph model generalizes the stochastic block model. An example of a problem in machine learning and statistics is how to recover the original graph limit given a sequence of samples from the model. There is active research work on this problem (although it is not the subject of my own research).

The mathematics underlying the theory of graph limits, notably the proof of their existence, hinges on Szemerédi’s graph regularity lemma. So these two topics are intertwined.

Sparser graphs

Graph regularity lemma and graph limits both have an important limitation: they can only handle dense graphs, namely, graphs with a quadratic number of edges, i.e., edge density bounded from below by some positive constant. This limitation affects applications in pure and applied mathematics. Real life networks are generally far from dense. So there is great interest in developing graph theory tools to better understand sparser graphs. Sparse graphs have significantly more room for variability, leading to mathematical complications.

A core theme of my research is to tackle these problems by extending mathematical tools on large graphs from the dense setting to the sparse setting. My work extends Szemerédi’s graph regularity method from dense graphs to sparser graphs. I have also developed new theories of sparse graph limits. These results illuminate the world of sparse graphs along with many of their complexities.

I have worked extensively on extending graph regularity to sparser graphs. With David Conlon and Jacob Fox, we applied new graph theoretic insights to simplify the proof of Ben Green and Terry Tao’s celebrated theorem that the prime numbers contain arbitrarily long arithmetic progressions (see exposition). It turns out that, despite being a result in number theory, a core part of its proof concerns the combinatorics of sparse graphs and hypergraphs. Our new tools allow us to count patterns in sparse graphs in a setting that is simpler than the original Green–Tao work. In a different direction, we (together additionally with Benny Sudakov) have recently developed the sparse regularity method for graphs without 4-cycles, which are necessarily sparse.

My work on sparse graph limits, together with Christian Borgs, Henry Cohn, and Jennifer Chayes , developed a new $L^p$ theory of sparse graph limits. We were motivated by sparse graph models with power law degree distributions, which are popular in network theory due to their observed prevalence in the real world. Our work builds on the ideas of Bela Bollobás and Oliver Riordan , who undertook the first systematic study of sparse graph limits. Bollobás and Riordan also posed many conjectures in their paper, but these conjectures turned out to be all false due to a counterexample we found with my PhD students Ashwin Sah, Mehtaab Sawhney, and Jonathan Tidor. These results illustrate the richness of the world of sparse graph limits.

Graph theory and additive combinatorics

A central theme of my research is that graph theory and additive combinatorics are connected via a bridge that allows many ideas and techniques to be transferred from one world to the other. Additive combinatorics is a subject that concerns problems at the intersection of combinatorics and number theory, such as Szemerédi’s theorem and the Green–Tao theorem, both of which are about finding patterns in sets of numbers.

When I started teaching as an MIT faculty, I developed a graduate-level math class titled Graph theory and additive combinatorics introducing the students to these two beautiful subjects and highlighting the themes that connect them. It gives me great pleasure to see many students in my class later producing excellent research on this topic.

In Fall 2019, I worked with MIT OpenCourseWare and filmed all my lecture videos for this class. They are now available for free on MIT OCW and YouTube. I have also made available my lecture notes, which I am currently in the process of editing into a textbook.

In my first lecture, I tell the class about the connections between graph theory and additive combinatorics as first observed by the work of Issai Schur from over a hundred years ago. Thanks to enormous research progress over the past century, we now understand a lot more, but there is still a ton of mystery that remains.

The world of large graphs is immense.

Back to main | List of entries |

More posts:

- Mehtaab Sawhney wins Clay Research Fellowship 1/25/2024

- Papers by MIT combinatorialists—Fall 2023 12/22/2023

- Schildkraut: Equiangular lines and large multiplicity of fixed second eigenvalue 3/6/2023

- Nearly all k-SAT functions are unate 9/19/2022

- Kwan–Sah–Sawhney–Simkin: High-girth Steiner triple systems 1/13/2022

- Graphs with high second eigenvalue multiplicity 9/28/2021

- Enumerating k-SAT functions 7/21/2021

- Mathematical tools for large graphs 7/12/2021

- How I manage my BibTeX references, and why I prefer not initializing first names 7/4/2021

- The cylindrical width of transitive sets 1/28/2021

- Ashwin Sah and Mehtaab Sawhney win the Morgan Prize 10/29/2020

- Jain–Sah–Sawhney: Singularity of discrete random matrices 10/13/2020

- Gunby: Upper tails for random regular graphs 10/5/2020

- Joints of varieties 9/12/2020

- Ashwin Sah's new diagonal Ramsey number upper bound 5/20/2020

- Joints tightened 11/21/2019

- Equiangular lines with a fixed angle 7/30/2019

- Impartial digraphs 6/27/2019

- A reverse Sidorenko inequality 9/26/2018

- The number of independent sets in an irregular graph 5/12/2018