Blog

Back to main | List of entries |

Impartial digraphs

June 27, 2019

I just finished a new paper, Impartial digraphs, coauthored with Yunkun Zhou, who just completed his undergraduate studies at MIT and will be moving to Stanford to start his PhD this fall.

The problem (along with the conjecture that we proved) was proposed by Jacob Fox, Hao Huang, and Choongbum Lee. Ron Graham had also told me about this problem with much enthusiasm during tea time one afternoon at the Berkeley Simons Institute a couple of years ago, after learning about it from Jacob.

I really enjoyed working on this paper with Yunkun. The problem is natural and simple to state, the answer appears somewhat unexpected (at least initially), and the solution ended up being quite tricky yet clean, employing a variety of tools in combinatorics, ranging from analytic methods (graph limits), algebraic considerations (polynomial identities and factorization), as well basic combinatorial techniques such as bijections.

We are going to talk about directed graphs (which graph theorists like to abbreviate as digraphs). These are graphs where every edge is given an orientation.

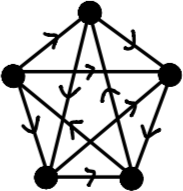

A tournament is a directed graph where there is a directed edge between every pair of vertices (think of it as recording the outcome of a round-robin tournament where every player plays against every other player).

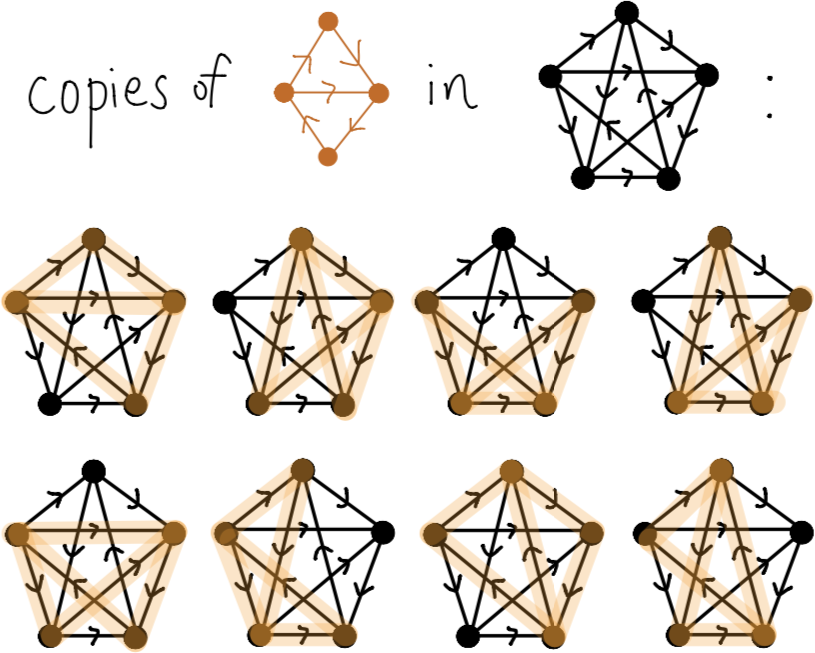

Given a directed graph H (think of it as a pattern), we can ask: how many different copies of the pattern H appear in a given tournament?

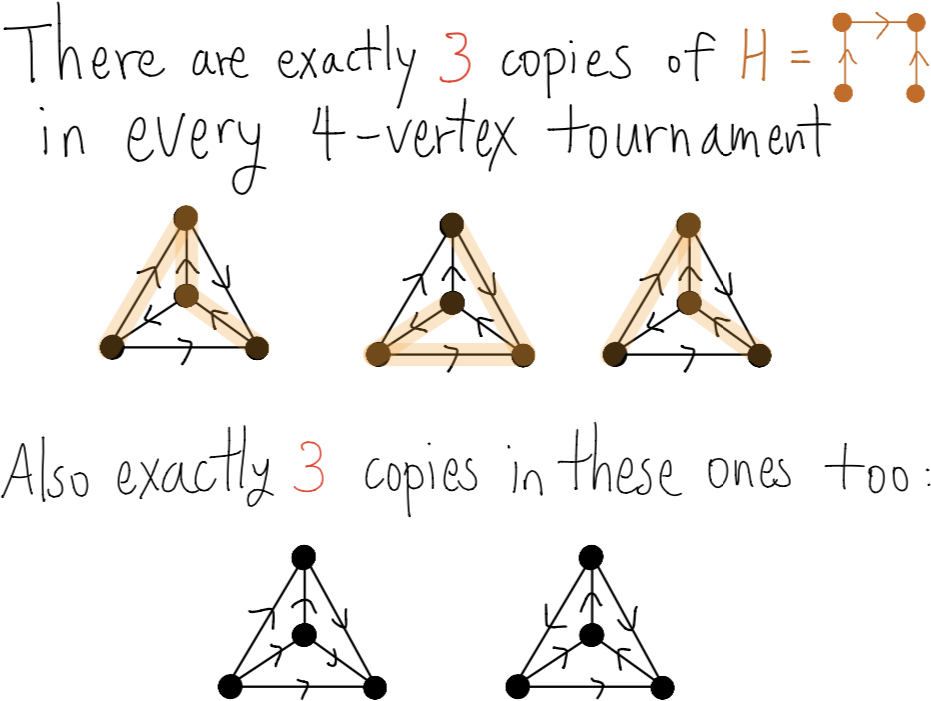

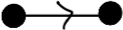

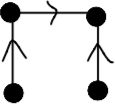

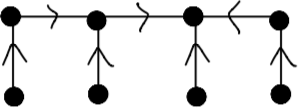

Look at the following 4-vertex tournament H. It has the following curious property: all tournaments of a fixed size contains the same number of copies of H, no matter how the edges in the tournament are oriented.

Hmm, why is this true? And are there other directed graphs H with the same property, namely that all tournaments of a given size contain the same number of copies of H?

In the good old mathematical tradition, we came up with a name for directed graphs H with this curious property: we called them impartial (as in: impartial judges of a tournament).

Okay. So why is the above directed graph impartial? Are there any other impartial directed graphs? What are all the impartial directed graphs?

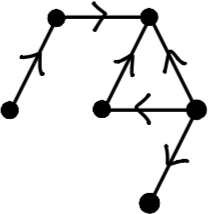

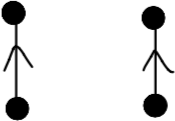

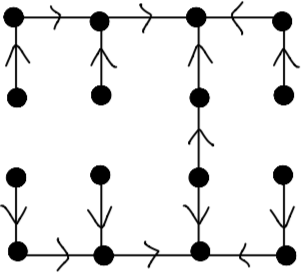

Here is a simple example of an impartial digraph:

Here is another one:

Indeed, given any 10-vertex tournament, we can count the number of copies of the first edge (it doesn’t depend on the tournament), and then count the number of copies of the second edge among the remaining 8 vertices (it still doesn’t depend on the tournament).

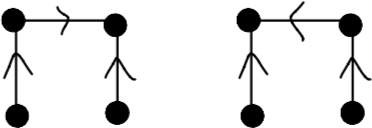

Once these two edges are placed in a tournament, there are two ways to join their tips, but they result in identical patterns (one flipped from the other):

It must then follow that this directed graph is impartial as well:

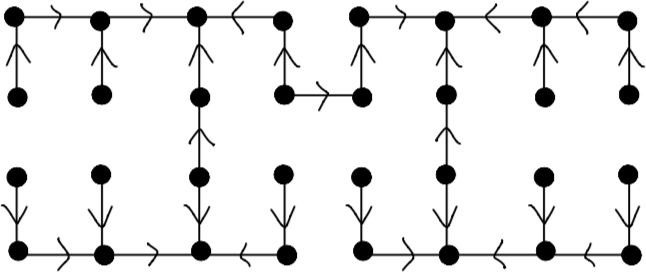

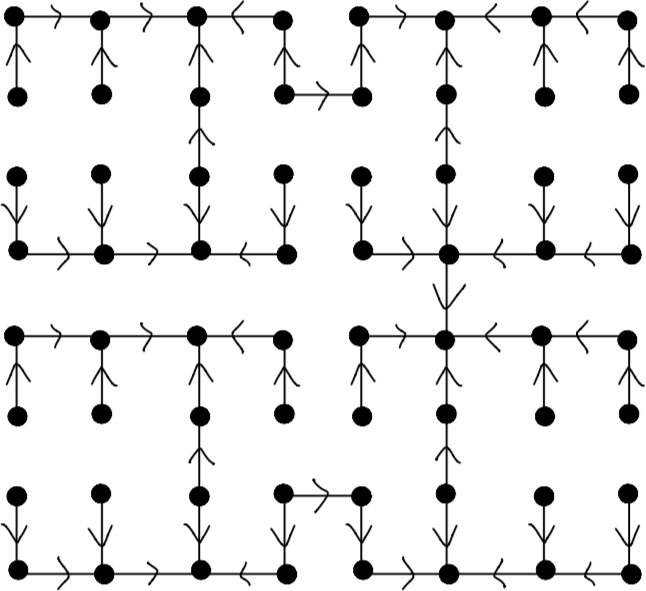

We can follow the same logic and continue this procedure, iterate, and build up even larger impartial directed graphs. Each step, take two copies of the previous tree (keeping the same edge orientations), and then add a new edge between a twin pair of vertices.

We call any directed graph that can building up as above a recursively bridge-mirrored tree.

The same argument as earlier shows that every recursively bridge-mirrored tree is impartial.

Are there other impartial digraphs? Did we miss any?

It turns out, there are actually no others. We have found them all, and that is the main result of our paper:

Theorem. A directed graph is impartial if and only if every component is recursively bridge-mirrored trees.

Just a word about how about this problem is related to a bigger picture. It is related to a number of other graph homomorphism inequalities that are central in extremal graph theory. It can be considered as the “equality case” for a directed analog of an open problem known as Sidorenko’s conjecture. See our paper for some further discussions and open problems.

Back to main | List of entries |

More posts:

- Mehtaab Sawhney wins Clay Research Fellowship 1/25/2024

- Papers by MIT combinatorialists—Fall 2023 12/22/2023

- Schildkraut: Equiangular lines and large multiplicity of fixed second eigenvalue 3/6/2023

- Nearly all k-SAT functions are unate 9/19/2022

- Kwan–Sah–Sawhney–Simkin: High-girth Steiner triple systems 1/13/2022

- Graphs with high second eigenvalue multiplicity 9/28/2021

- Enumerating k-SAT functions 7/21/2021

- Mathematical tools for large graphs 7/12/2021

- How I manage my BibTeX references, and why I prefer not initializing first names 7/4/2021

- The cylindrical width of transitive sets 1/28/2021

- Ashwin Sah and Mehtaab Sawhney win the Morgan Prize 10/29/2020

- Jain–Sah–Sawhney: Singularity of discrete random matrices 10/13/2020

- Gunby: Upper tails for random regular graphs 10/5/2020

- Joints of varieties 9/12/2020

- Ashwin Sah's new diagonal Ramsey number upper bound 5/20/2020

- Joints tightened 11/21/2019

- Equiangular lines with a fixed angle 7/30/2019

- Impartial digraphs 6/27/2019

- A reverse Sidorenko inequality 9/26/2018

- The number of independent sets in an irregular graph 5/12/2018